History

Videos

History 1896-1930

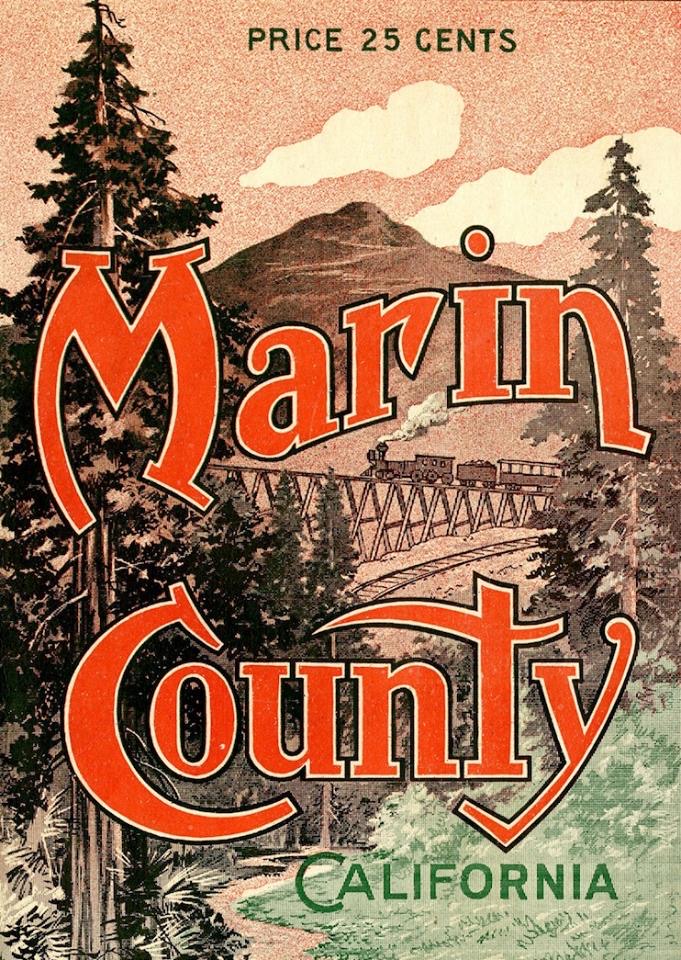

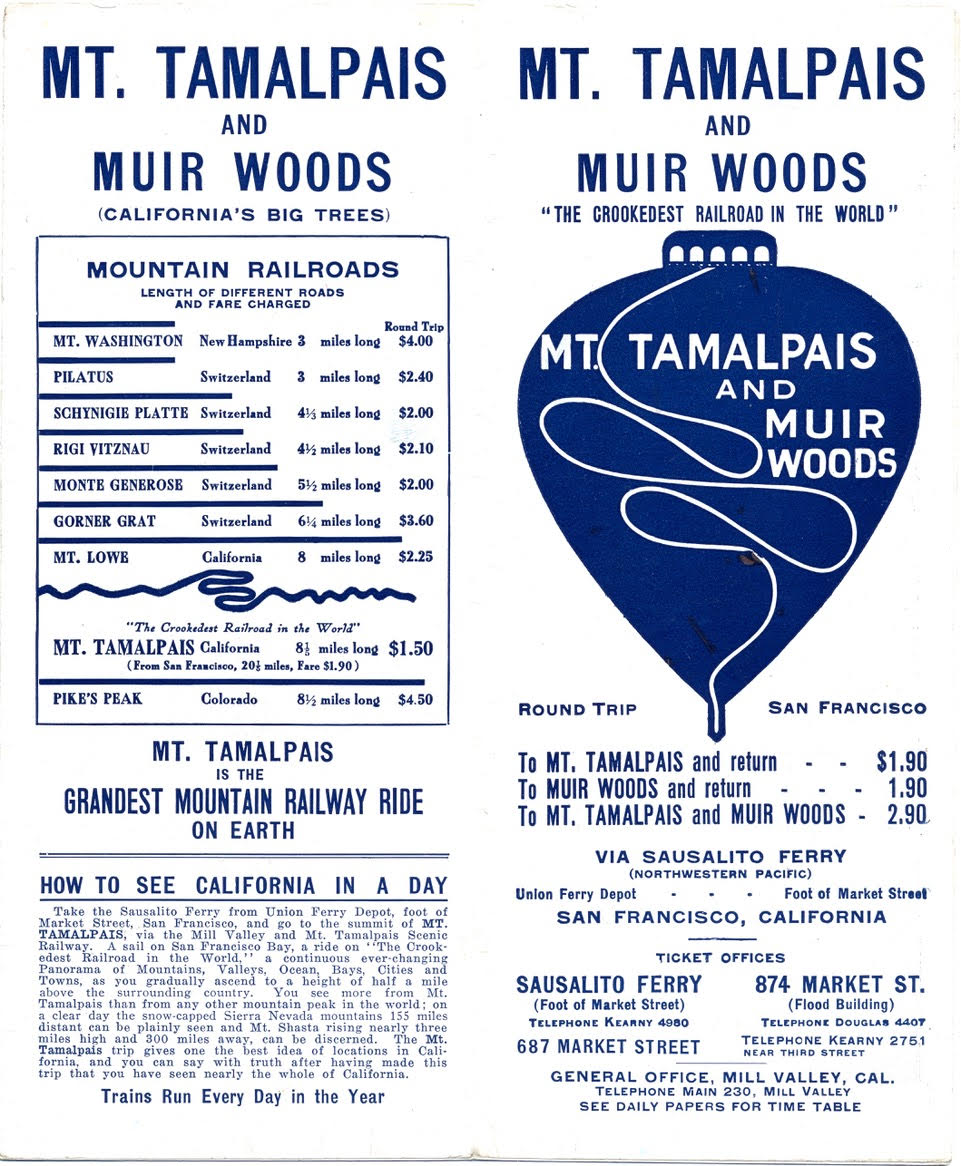

Construction of the “Crookedest Railroad in the World” began on February 5, 1896. There is no clear account of when engineering and surveying began, but undoubtedly that occurred some time before. The last spike was driven on August 18, 1896. The first passenger train with Mill Valley citizens aboard went up the mountain on August 22,1896. A festive press train overflowing with journalists ran on August 26. The Grand Opening was August 27.

Construction details

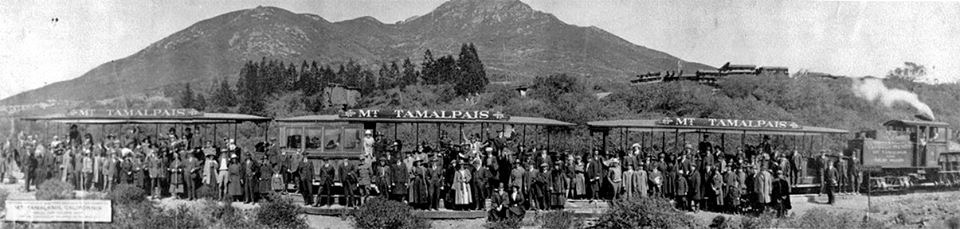

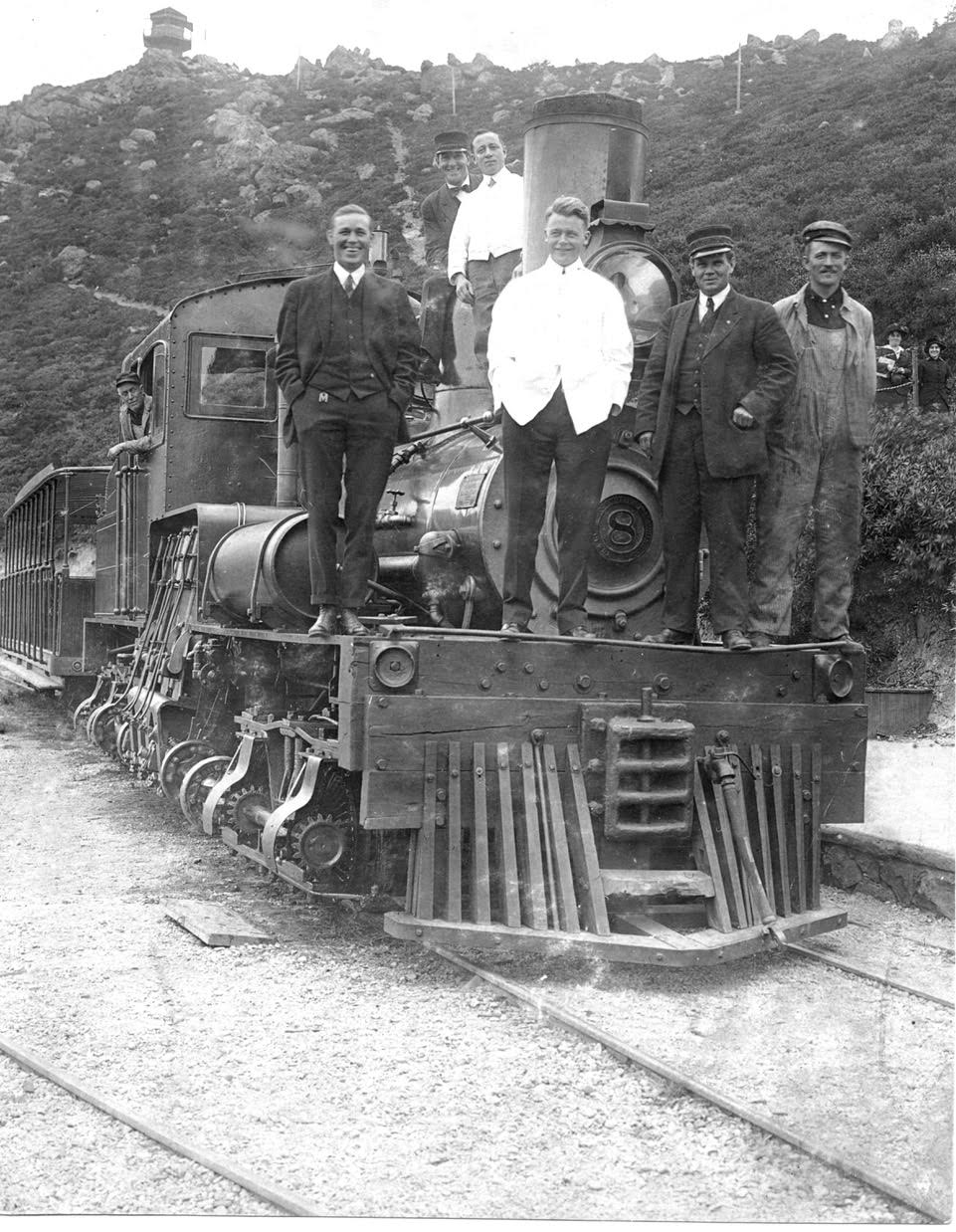

The original railroad road bed of the Mill Valley & Mt. Tamalpais Scenic Railway was 8.19 miles long with 22 trestles and 281 curves. The longest straight stretch was in the middle of the Double Bow Knot, the halfway point, a distance of 413 feet. The rails were 57 pound steel with redwood ties. Work crews averaged 200 men, mostly European immigrants, who carved the railroad grade by hand with picks, shovels, wheelbarrows and blasting powder from mountain rock. The cost of construction was reported to be $55,000, with another $80,000 for equipment. Original equipment consisted of one Shay engine of 20 tons, one Heisler engine of 30 tons, six open canopied cars, one San Francisco cable car and two flat cars. Regular operations began August 27, 1896. The grade averaged 5% while the steepest part, just down the grade from the summit a short distance, was a “modest” 7%.

When the rails had been laid, the Railroad began construction of the Tavern of Tamalpais, a place of food, drink and hospitality near the summit. There was a spectacular view of San Francisco Bay and Pacific Ocean from the shingled white building. A popular place, it was quickly overrun and the Tavern was enlarged by over 30 rooms in 1900.

In 1902, the Railroad built a stage road from West Point to Willow Camp (Stinson Beach) to see if passengers were interest in the route. If there was enough business they would lay tracks to the beach. Stage service began in 1903. In 1904, the West Point Inn was built to be an amenity for those passengers in bad weather. Very quickly the Inn became popular with hikers. (Tracks were never laid and stage service ended in 1915.)

The railroad was part of creating Muir Woods with its employees helping to build and maintain trails and guide guests through the primeval redwood grove. It was the last stand of virgin redwoods near a major city when William and Elizabeth Kent purchased the canyon and save it from being logged and dammed in 1905.

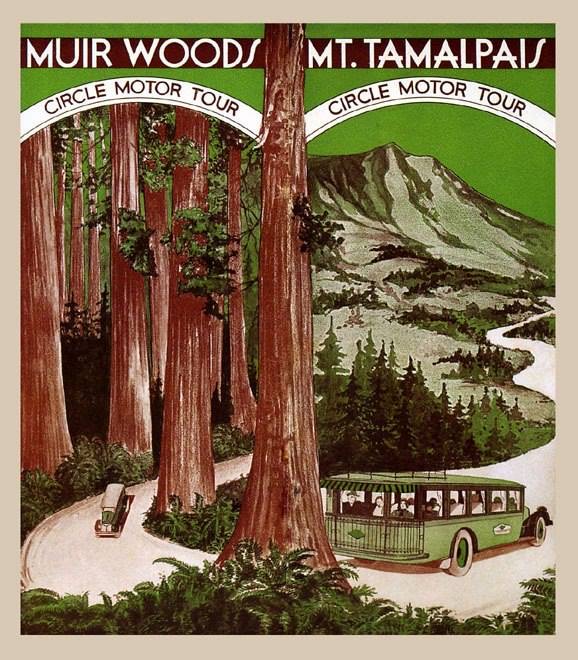

Construction of a branch line to Muir Woods began in late 1906 and finished in spring 1907. About 2 miles long, it ran from Mesa Station on the Double Bow Knot to upper Muir Woods, with a grade varying from 4% to 7%. The scenic railway carried the first tourists to Muir Woods, including naturalist John Muir. President Teddy Roosevelt declared the canyon a National Monument in 1908, and the railroad built a rustic inn on the edge of the park, a building first proposed by William Kent (not yet Congressman Kent). Muir Woods became (and still is) a very popular destination.

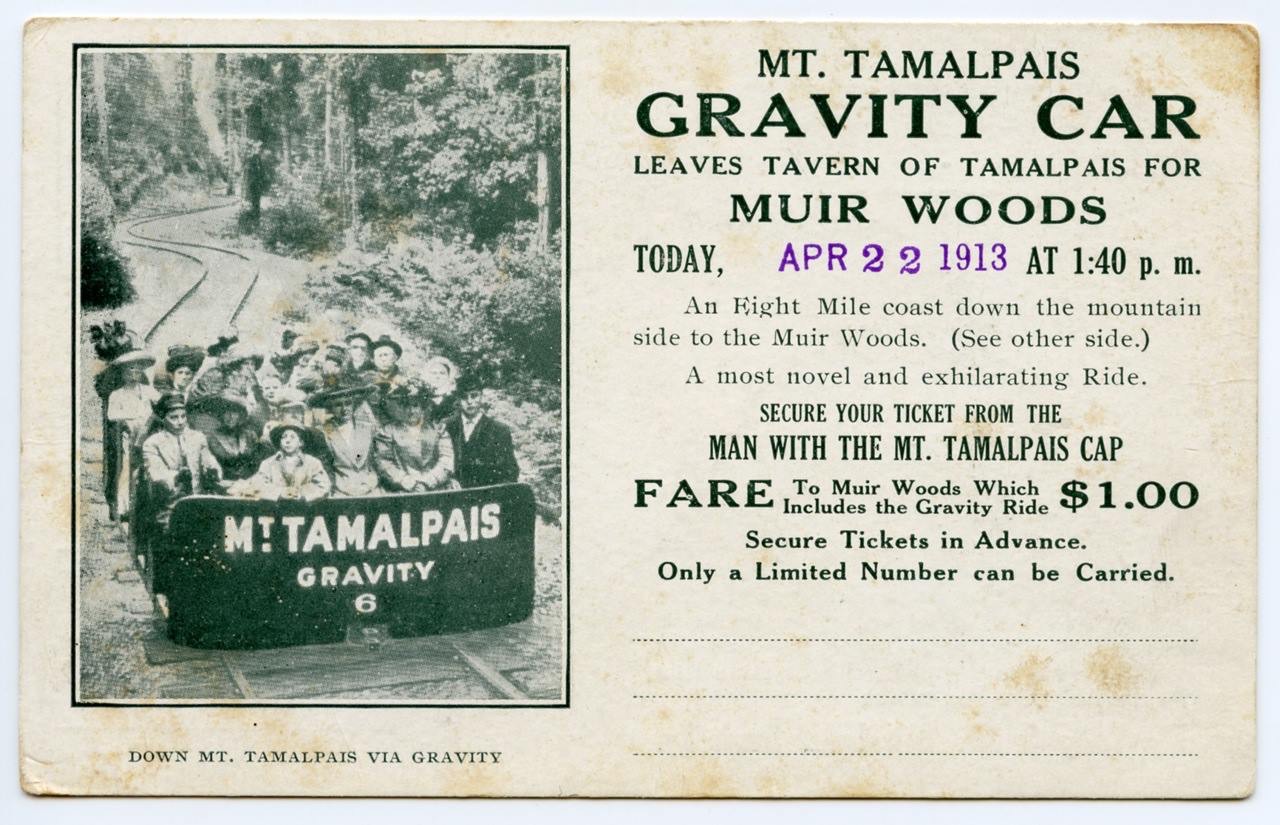

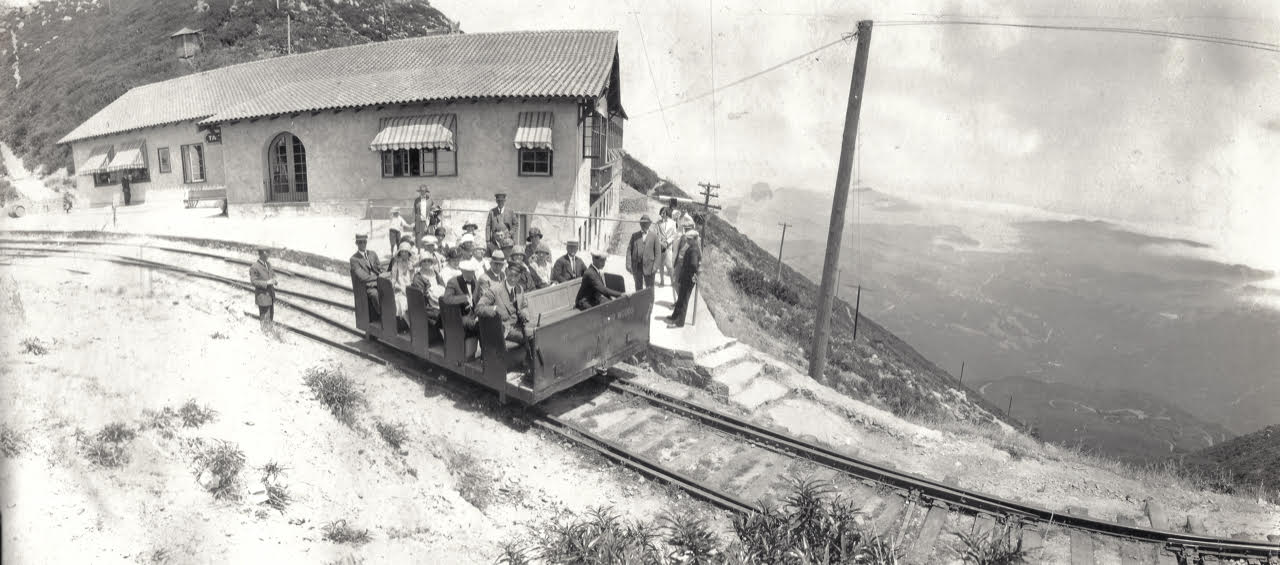

Unique to Mt. Tamalpais were the Gravity Cars, simple 4-wheel coasters, “powered by gravity,” that carried guests safely from the summit into Mill Valley and later in to Muir Woods. (Learn about Gravity Cars at the Gravity Car Barn.) Additional cars and engines were purchased at regular intervals and some of the first equipment was sold later to find use in northwest logging operations.

Running Backwards

Unlike railroads running on level ground, the safest way for a mountain railroad was for the engine to push the cars up the mountain. When the cars came down with an engine, the engine led. The trains never turned around. This had obvious safety advantages, and according to accounts of the time it also provided better viewing ahead when the train was ascending. An added bonus was that when the engine worked its hardest climbing the mountain, the exhaust was behind the train and not in the passenger’s faces. This procedure and the other safety measures worked to a remarkable degree for there were no passenger lives lost during the entire period of the railroad operation. Two men associated with the railroad were killed. One was scalded to death in an accident involving an overturned engine. The other was killed in a head- on collision between two trains, but that was down in Mill Valley, not on the mountain proper.

A second gasoline powered motorcar was built in the Railroad Shops in Mill Valley and put into service in 1912. The car had two speeds in either direction and could reach 25 MPH on the return climb from Muir Woods. The Muir Woods Branch, listed on modern maps as “Gravity Car Grade,” passed through the Mine Ridge cut at the Mountain Home Inn where there was a pipeline truss bridge suitable for hikers about 30-feet above the railroad’s tracks.

Running steady

The Railroad was reorganized in 1913 as the Mt. Tamalpais and Muir Woods Railway. The company had 6 locomotives including 5 Shays, 19 wooden open cars, 16 Gravity Cars plus 7 other cars and coaches. The Gravity Car time schedule from the Tavern down was 8 minutes to West Point, 12 minutes to Double Bow Knot and 14 minutes to Lee St. Station.

After a run down the mountain Gravity Cars were pulled back to the summit by a locomotive – that is, downslope, below the engine. One of the many safety rules in effect for railroad operations was that towed “Gravities” could not be occupied by customers. However, a railroad employee was in each Gravity Car to set the brakes should the car ever brake loose. Detailed safety regulations as regards speed, number of passenger-occupied cars per engine, sand introduction to clean the flues and many others were developed and must have been very effective considering the safety record of the Railroad.

Water for the boilers, for cooling the wheels and for the tavern operation was a major operating concern. All engines and Gravity Cars had a small tank just for applying a small jet of water to cool the wheels and brakes. A tank car was devised initially for the purpose of hauling water to the tavern from the Fern Canyon water tank. Later, a pumping station was installed about half way down the Fern Creek trail to pump water to the Tavern. This station continues to pump water to East Peak today. A normal train trip up the mountain would include filling the tanks at the yard, a stop at Mesa Station for water and another stop at Fern Canyon.

Fire on the mountain

The first disaster occurred in 1913. A major fire raged for 5 days and charred the mountain’s southern face from West Point to East Peak. Presidio troops were called out the first day and before the fire was contained more than 7000 firefighters were engaged in the fight. One San Francisco newspaper stated that Mill Valley was doomed. Amazingly, no railroad equipment or buildings were lost although several engines and cars were scorched. The railroad and its crews contributed significantly to controlling the fire.

In 1915 the railroad carried an average of 700 passengers per day during the summer and handsome profits were realized. The War in Europe had a negative effect on operations in 1917 and 1918, as did the 1918 Spanish Flu epidemic, but by 1920, when the last locomotive, No. 9, was purchased, things were booming again. The Tavern burned down in 1923, but was soon rebuilt on a less grandiose scale. The trains continued to run even when there was no tavern. When the Tavern was rebuilt it was designed to serve both railroad and auto passengers who began to arrive in 1925.

Winding down

The railroad continued to operate, although less actively until the great fire of July 2, 1929. That fire was a near disaster for some of the equipment and the crews. Again the railroad was a critical factor in fighting the fire. Crews on the mountain were in great jeopardy and some equipment was lost. One engine was abandoned and all the woodwork was burned away. It was towed back to Mill Valley and not returned to service. Oddly enough the railroad was put back into service shortly after the fire, but closed permanently in 1930. Tracks were pulled up and sold. Engines were sold, mostly to logging companies. Two engines went to the Philippines. (Engine No. 9, the only piece that survives, is currently being restored by FriendsOfNo9.org.) The fire was an important factor in the decision to shut the line down, but the real culprit was the automobile. It clearly signaled the end of an era.

Content courtesy of Robert Larson.

(Update by Fred Runner, July, 2020)

Further reading:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mount_Tamalpais

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mountain_biking_on_Mount_Tamalpais

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Streptanthus_batrachopus